In this article, we shall be examining how to do data collection and analysis of your data. Remember that data is what you are going to test to either prove your hypothesis or consider it false. In case you are working with research questions, your data will enable you to get the answers you aim at achieving. Let me quickly mention here that your research aim must be clearly stated before proceeding with your research.

Data Collection

If your research is empirical requiring test of a hypothesis like the one that tests how I00 level students respond to indirect speech act, then your data will normally be elicited. In that case you will be careful to design the elicitation experiments to ensure you elicit the kind of response (i.e. the data) that will measure what you are testing. Remember that you must eliminate all irrelevant variable and do not manipulate your data to prove your hypothesis. Very often, good data analyses always prove certain hypothesis wrong. It is necessary that while you are recording a conversation, the participants should not know that they are being recorded; otherwise you may not get a natural conversation. Although, you may need some information about the interactants which you may not get in the conversation, thereby requiring you to talk to them individually. In that case, you may have to talk to them and seek their permission to use their conversation for academic purposes. This will take care of an ethical issue that forbids you revealing data provided by informants without their consent. So you have to decide whether to obtain the from prior consent of your informants before collecting your data, or ask their permission to use data after they have been collected or not to ask permission at all (Grundy, 2000). Your decision will depend on the circumstances where the data are collected and the kind of conversation involved.

You may be collecting data that require interviews or questionnaires. You either decide to record the interview and transcribe it later or carry out a structured interview where you write down the interviewee’s responses. Whether you are collecting data from elicitation method, interview or questionnaire, your raw data is essentially the pattern of naturally occurring language use by speakers in their socio-cultural or institutional contexts that will enable you to make some judgements as to whether your hypothesis is right or wrong.

Therefore there is no research without available data and it must be presented in the work, either qualitatively or quantitatively (i.e. involving figures, tables, graphs etc.) It is wrong therefore to go on to describe patterns of turn-taking in a conversation or discourse structures of some data without presenting them for us to see. Some students go on to do some “analysis” and then bring in bits of what they call data here and there in the analysis without presenting the data itself first.

If you are doing a study of written communication, the parts of the material that serves as your data must be copied out. If they are adverts, news headlines, cartoons, stickers etc. you must endeavour to present the written version of the data and where necessary (as in adverts) original copies should be attached as appendices. Remember that our attention here is language use – that is why it is linguistic research and we are testing how meaning is generated, processed and disseminated in the context of users and situations.

In summary Grundy (2000) gives us some points to note especially if data collection is such that aims at testing some hypotheses:

(i) Whenever possible, do a pilot collection exercise first to enable you see whether the data you are collecting is audible and transcribable or useful for the purpose you have in mind.

(ii) Consider whether you need to use all the data or just some part of them. Sometimes excluding any part of the data may render them an incomplete record of speech event recorded.

(iii) Don’t be too ambitious: one hour of conversation involving several speakers can take many days or even weeks to transcribe. So limit the amount of data you set out to collect to what you can practically transcribe and adequately analyse.

(iv) Ensure that your data contains the information you need. Nothing is more frustrating than to have data which do not really reveal what you had hoped they would or that are difficult to hear and transcribe.

Analysing/Interpreting Data

Analysis is the breaking down and ordering of the data (quantitative information) involving searching for trends and patterns of association and relationships among data or group of them. Interpretation involves the explanation of the associations and relationships found in the data, including inferences and conclusions drawn from these relationships.

Let’s assume your research is the activity type investigating the structures and pragmatic properties of seminars/interviews or such that focus on power and distance. You will be required to identify from the data how the speech events are goal oriented and whether they determine their own structures or not; how expectations are signalled, implied and referred to;

- how talk is constrained and how participants indicate constraints on allowable contributions; how functional roles assumed by a speaker and assigned to another speaker are determined etc.

- how power and distance are encoded;

- how speakers and hearers use politeness strategies to acknowledge the face want of others;

- how properties of discourse perform speech acts, construct identities, reflect societal norms, beliefs or ideologies; how implicatures signal culture-based meaning; etc.

Your data is likely to reveal much more depending on how successful your data collection procedure has been.

Your analysis may require that you put certain information in figures or tables or workout some percentages, especially if your research is quantitative arising from an empirical method. Sometimes your analysis may also demand that you identify some analytical categories in which case, you break your analysis into sections or sub-sections. Your analysis must stick to the overall goal of the research and must be able to answer your research questions positively/negatively or prove/disprove your hypotheses.

It is important to mention here that in linguistic (or pragmatic) research; we do not generally edit our data before analysis as is the practice in some disciplines. We may “edit” some wrong figures, involving names or numbers but certainly not the actual discourse samples of respondents. Whatever variety of language use you obtain is very essential even where they are idiosyncratic.

What some people call “errors” in language use are indeed indicators of variables that reveal a lot about speakers, their social identities, statuses, beliefs etc. Again I would like to warn against manipulating your data; trying to “correct” what an informant/respondent said. As long as we are testing language habits and how they occur in their natural settings, constructing values, identities, societies; sometimes how these mediate attitudes and perform social actions, we have no choice than to leave the raw data the way it is.

Some students have also been found to generate some “data” all by themselves, for instance, someone doing a study of bumper stickers and writing some stickers herself in order to complete the number she wants and then coming back to say she collected them from the field. This is absolutely dishonest. Stick to your data and where you have some difficulty in your analysis, consult your teacher or supervisor. You will notice that this section on doing pragmatics have concentrated on some key issues about linguistic research and do not cover all you need to know about research and its technicalities. It is assumed that you have done a course on research methodology.

Methodology

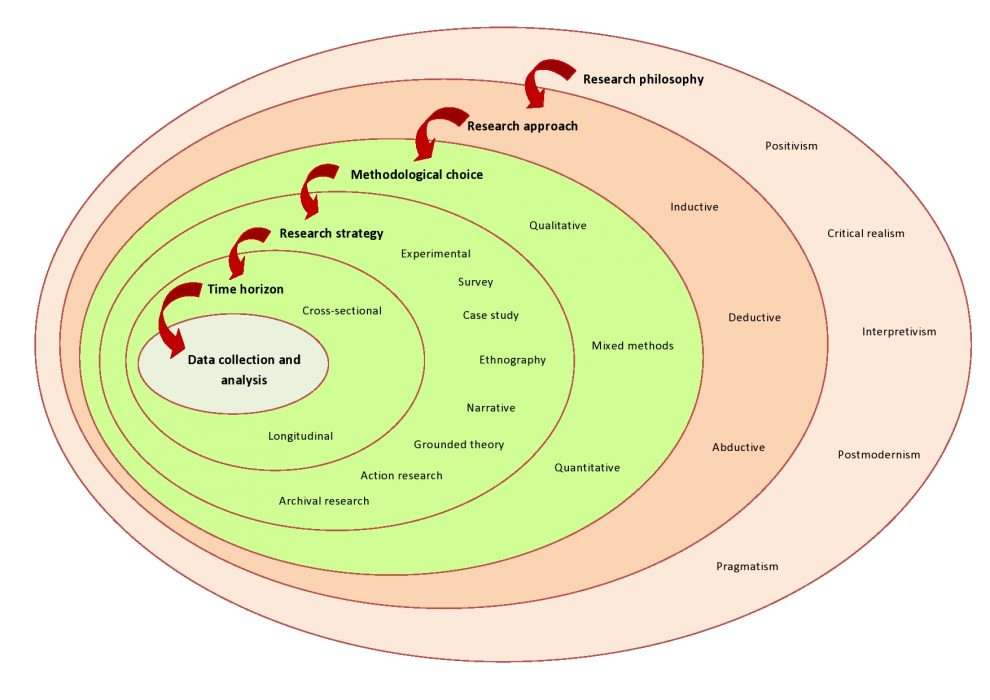

Methodology is about how you intend to do your analysis. If you are applying a scientific method of analysis involving experimentation, transcription of data, analysis of questionnaire etc where your result will demand some figures and statistics, then it is quantitative. If it is descriptive, which involves your own judgement and interpretation of the data based on some inferences etc, then it is qualitative. You will need to state this clearly in your work.

Your methodology is usually determined by the theory you adopt in your analysis. If you are investigating patterns of speech acts in news headlines for example, you will need to clearly define and explain the speech acts theory and why you think it is the most appropriate in the study of language use of news headlines. Naturally, your analysis will be the qualitative method where you will do a descriptive kind of analysis. At your level, however, your supervisor will guide you as to how you approach the matter of theory and methodology.

Reporting Findings

What you report as your research finding is the actual outcome of your research, not your hypotheses. Some students attempt to force their research questions or hypothesis into their findings whether or not findings justify their hypotheses. As we said earlier, your findings do not have to prove your hypotheses or answer ‘yes’ to your research questions. Your concern is to do your investigations and report your findings objectively. It is your findings that determine your final conclusions and possible recommendations. At this point, the reader will be able to see clearly the contributions your research has made. Always do a thorough citation at the end. Your bibliography must reflect all the materials you have used in the Work.

CONCLUSION

We can then conclude that pragmatics is a practical exercise that reveals the many dimensions of language use and the various levels of meanings they generate in social contexts. Pragmatics is an exercise in search of meanings. Much of these “meanings” are actually a revelation of ourselves – our intentions and tendencies; our identities, relationships, cultures and beliefs; our hopes, our strengths and our weaknesses. So every effort in pragmatic research provides an opportunity to understand better the nature of language, how it works and what it means to us.